Two Countries / Two Kibei

Two Countries / Two Kibei

Two Countries / Two Kibei

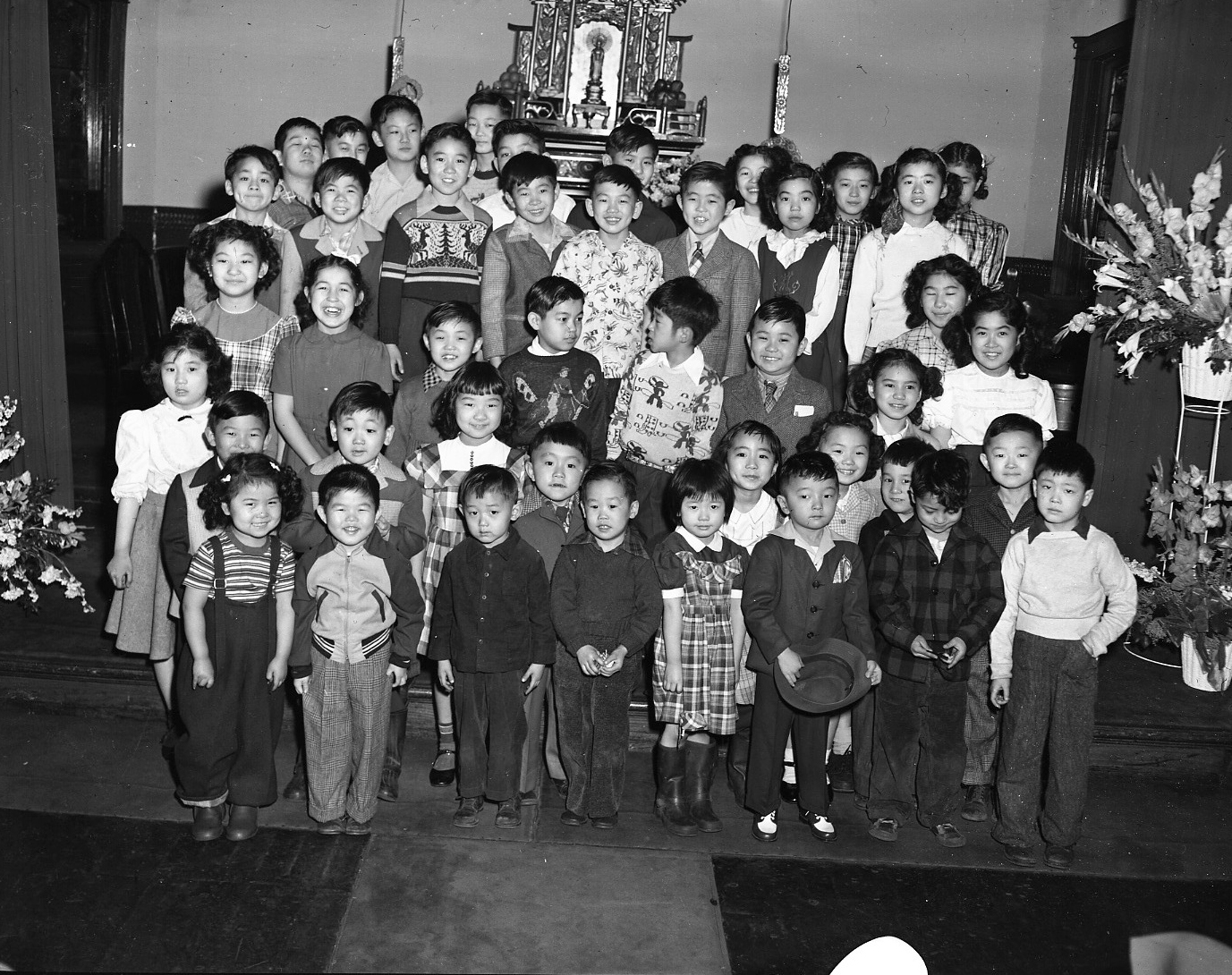

During the 1930s, it was the practice of some Issei – first generation Japanese Americans – to send their children back to Japan to attend school, live with extended family, and absorb the culture and language of their parents. The intent was for the young people – called Kibei – to return to the United States; and as of 1942, nearly 10,000 had come home to this country. That number did not include, however, many students – natural born American citizens – who were stranded in Japan during World War II. Some eventually returned to the United States after the war, though the bureaucratic repatriation process was difficult indeed. Others remained in Japan, either unable to cut through the red tape or preferring to stay in their adopted country. Many who stayed never felt fully Japanese, but at the same time, they feared they would never again feel comfortable living in America.

This is the story of two Kibei. One returned to the United States before the war, while his family remained in Japan; the other planned to return, but the war intervened. She and her family corresponded regularly after hostilities ceased, but she never came back to the United States, except to visit.

The original images shown in Two Countries / Two Kibei are in the JASC Legacy Center. All Numata photographs are from the Mary and James Numata Photograph Collection, and all Yamamoto images are from the Yamamoto Family Photograph Collection.

James Numata

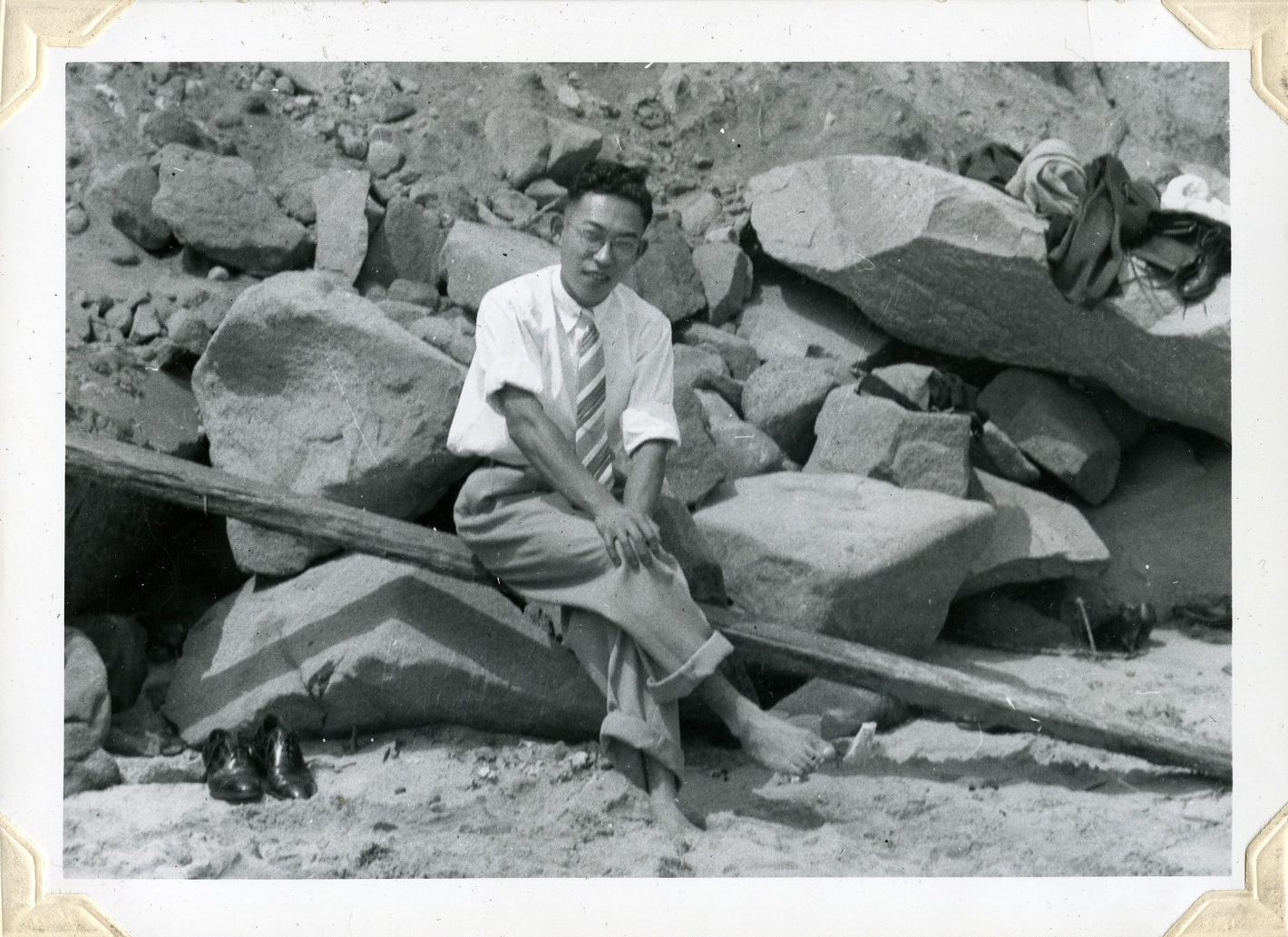

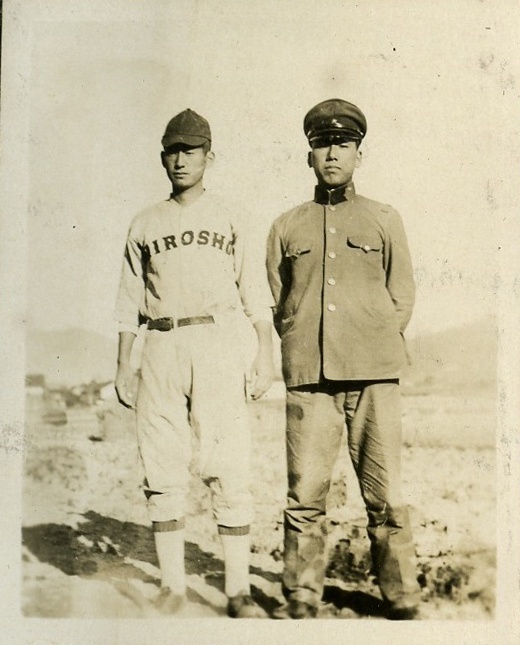

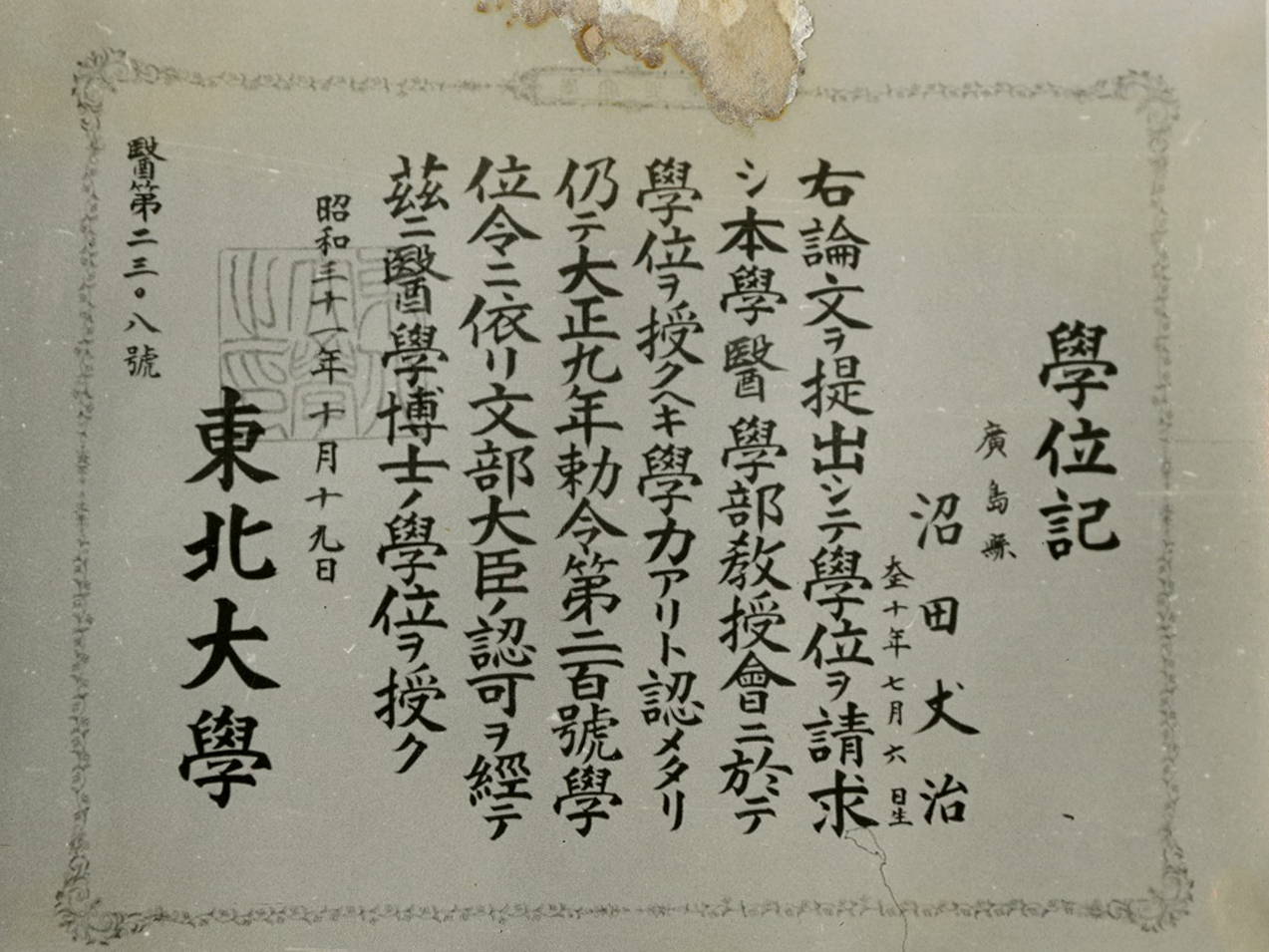

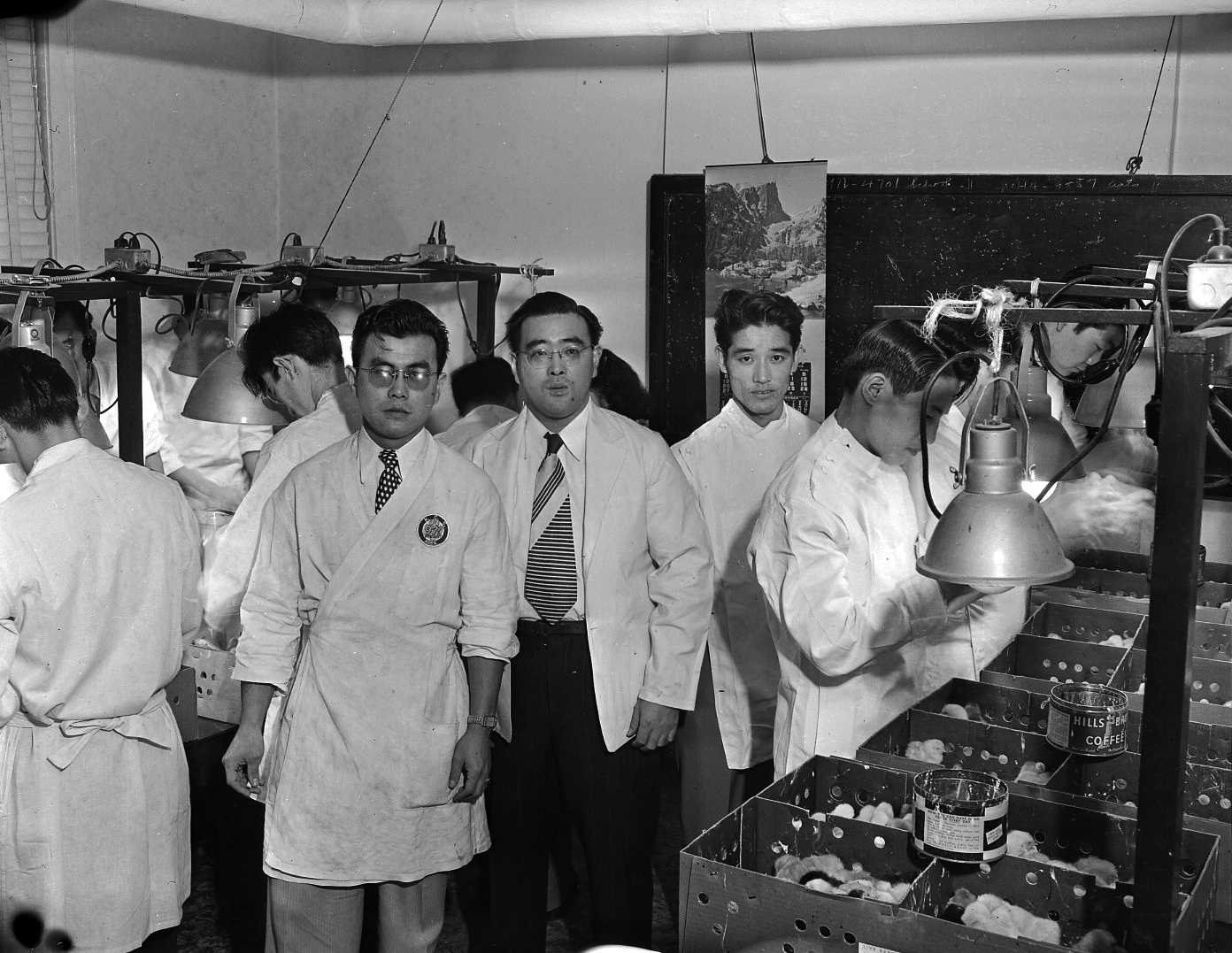

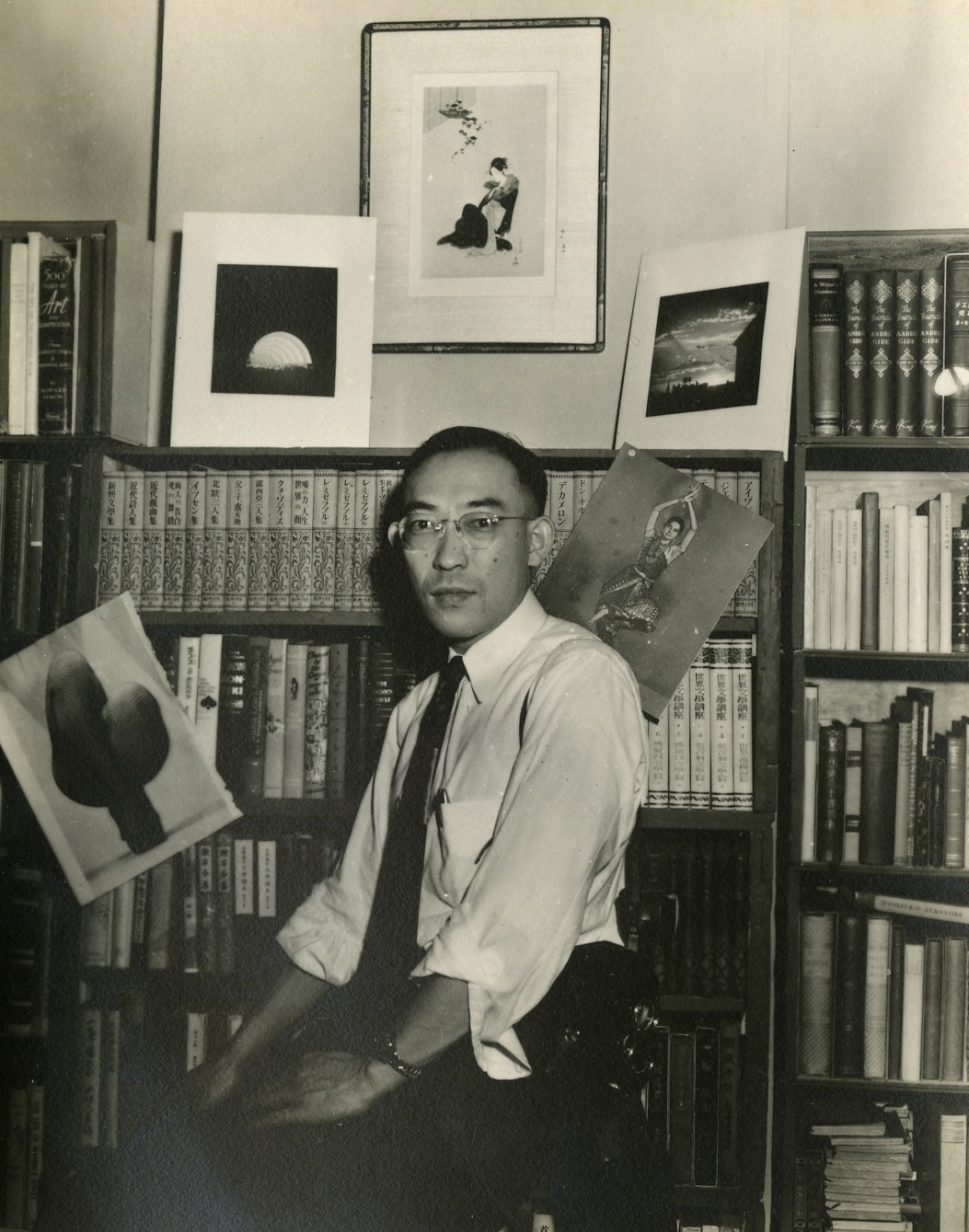

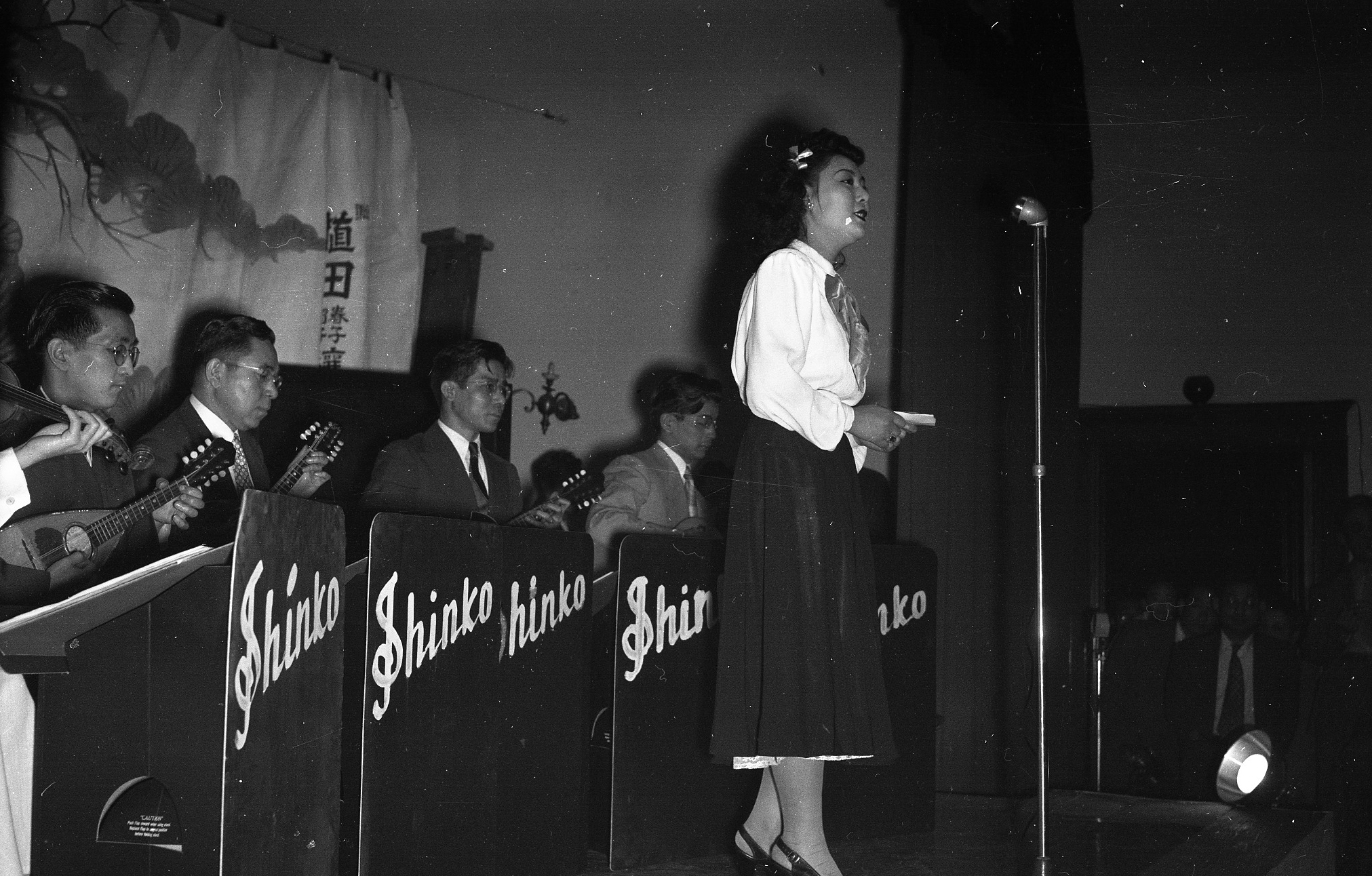

James Shizuo Numata was born in Devil’s Slide, Utah, in 1918, to Shuichi Numata, a farm worker, and his wife Hamano. Seeking economic opportunities and Japanese education for their children, the Numata family returned to their home city of Hiroshima in the mid 1930s. With the exception of James, the family never returned. James’s brother George remained in Japan. He earned a medical degree and established the Numata Children’s Hospital in Hiroshima after the war. James, on the other hand, moved back to California before the war, was interned as a Kibei at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, and resettled in Chicago upon release from the camp. Though little of his written record remains, he documented his life and community through his camera. By the time he died in 1997 in Chicago, he had accumulated some 10,000 images now housed in the Legacy Center of the Japanese American Service Committee.

Yuki Yamamoto

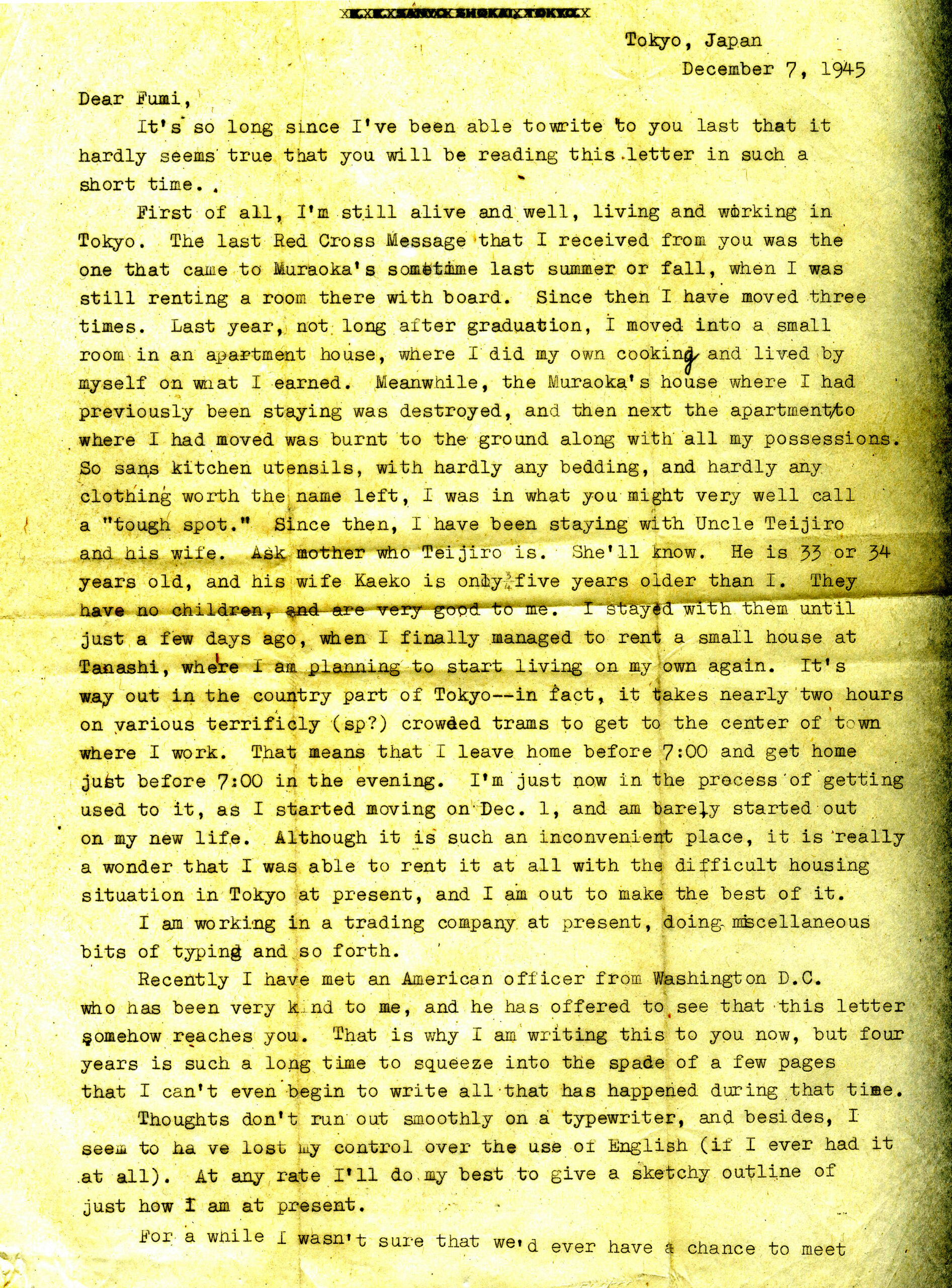

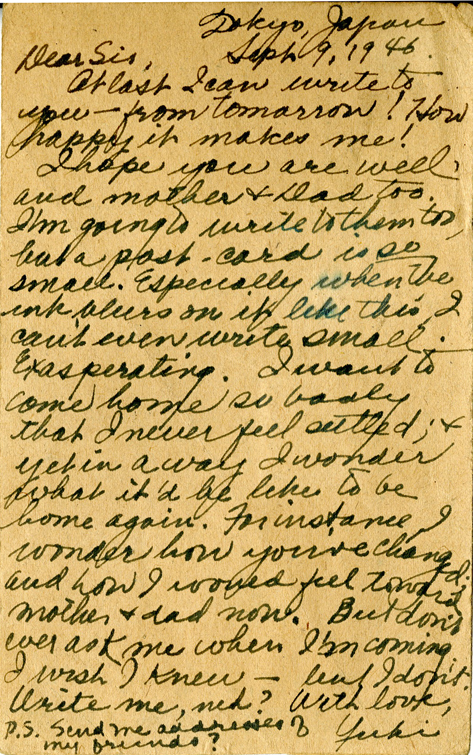

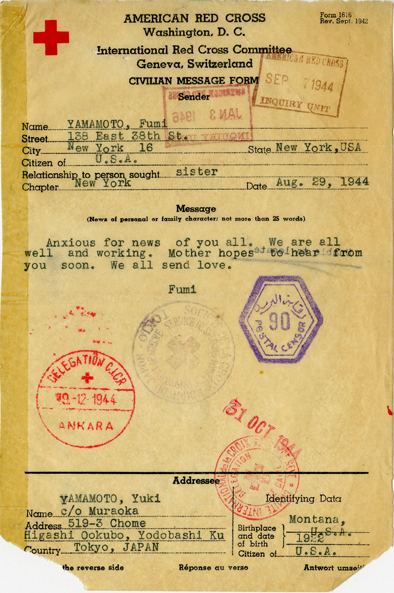

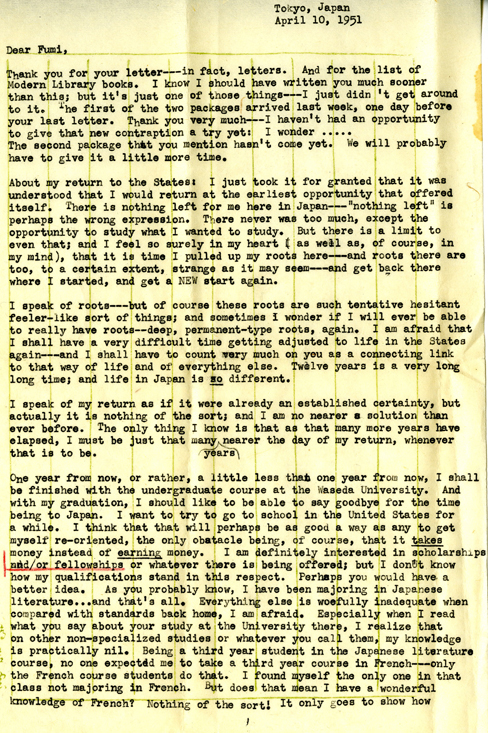

Yuki Yamamoto was born in Whitefish, Montana, in 1922, Jinzo Yamamoto, a railroad worker, and his wife Cho, recently arrived from Japan. The family moved to Spokane, Washington in the 1930s and opened a Japanese market, later a café. After graduating from high school in 1940, Yuki sailed for Japan to further her education. She did not return before the attack on Pearl Harbor, and she spent the duration of the war in Osaka, then Tokyo. Toward the end of the war, in order to be able to work, she registered as a Japanese citizen, an action that made it difficult, if not impossible, to return to the United States. She made several attempts to obtain permission from the U. S. State Department to return, but she was unsuccessful. At the same time, she was somewhat ambivalent about leaving Japan. She had numerous close friends there, and she became a successful journalist with the Japan Times. She never came back to the United States, except to visit, and died in Japan in 1987.